Christ the King

Sermon for Sunday, November 20, 2022

Of this Sunday, which is often called “Christ the King Sunday” or “The Reign of Christ,” one Anglican priest whom I will not name had the following to say:

“The Reign of Christ is a chance to think what the world might look like if everyone behaved like Jesus.”

This sentiment is completely wrong, in the worst way possible. The Reign of Christ is not about wishing for a better society, if only people would behave themselves. There are no ‘ifs’ about the reign of Christ. This Sunday's observance is not about better living through ethics, but about a King who rules the nations with a rod of iron, and who will bend all things to his gracious will.

Of course, it is tempting to compare the way the world is, with the way we would like it to be. You may have noticed that all is not well with the world today.

I want to explain something about the specific times in which we live. You may already have a sense of this, or have wondered about what is going on.

Our country, our society, in fact, the whole modern world, is experiencing an extended and acute crisis of authority, a crisis of institutional decline. This has been going on in some form for most of our lifetimes, but it is getting worse and worse.

For many in the postwar generation, raised in the righteous afterglow of the Second World War and the heroic fight against fascism, the Vietnam War was the first time they began to suspect that the people in charge were wrong, or didn't have the country's best interests in mind, or perhaps were simply wicked and cruel. And those veterans who returned from that conflict received, not the heroes’ welcome enjoyed by the GIs of 1945, but suspicion, abuse, and ostracism from their fellow citizens. Our society was divided.

For many of the baby boom generation, the real heroes, the real role models, were not elected officials, but activists, truth-tellers, iconoclasts; those who stood up to the power structures of the government, of polite society, even the church, to support justice and equality.

But while the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 70s achieved many of its goals, the various and sundry social movements which followed it were neither as successful nor as unifying—nor, indeed, as clearly righteous. Activist heroes and gurus who emerged from the 60s milieu proved no less fallible than other authority figures. Many became corrupt and abused their power and goodwill, and were co-opted by powers no less insidious than the ones they had opposed.

In the prosperous 80s and 90s, America abandoned idealism and turned to capitalism and consumerism as our cultural uniting values. Hippies became Yuppies, fretted about the antisocial tendencies of Generation X, and gave birth to my generation, the Millennials.

The reputation of capitalism took an initial hit with the collapse of the dot-com bubble in the year two thousand, followed by the Enron scandal, and government-chartered financial institutions went morally bankrupt less than a decade later in the subprime mortgage crisis.

In 2001, a new, external crisis in the form of terrorism provided a temporary infusion of confidence in our national institutions, particularly the military and the agencies of American interventionism. “Regime change” became fashionable again, even as the American regime embarked on unprecedented surveillance of its own citizens, domestic police forces adopted military weapons and tactics, and an ever-escalating series of supposedly high-stakes elections made political civility a fond memory, and both major political parties were captured by the lunatic fringe. Beginning with the 2000 election it became normal for the losing party in every presidential election to level allegations of systemic election fraud and voter disenfranchisement by the winning party.

A year after 9/11, the Boston Globe broke the story of the massive abuse scandal and the even more scandalous systematic cover-up in the Roman Catholic Church. The abuse, of course, was something we already knew about on some level, often emerging within our social consciousness as the subject of dark humor. But the cover up shook the faith of many Catholics who had been raised to believe in the authority of the Catholic Church and the infallibility of the Pope. Protestants and evangelicals, whose churches lacked the same degree of centralized authority, at first blamed these problems on the distinctive practices and structure of the Catholic Church, until all too soon they discovered flagrant abuse and cover-ups in their own midst. Today, the moral authority of all churches and religious leaders, not just Catholics, is in tatters.

By the second decade of the present century, people had lost their faith in Government, in the Church, in schools and institutions of higher learning, and in the free market.

But at least there was one trusted authority still above the fray: the voice of Science.

Until 2020, when the scientific and medical establishment proved that it, too, was both subject to fallibility and ethical failure. After months of contradictory public health recommendations and crippling lockdowns and mandates—all of which had little apparent effect in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic—the reputation of our public health authorities, and even of the medical profession, was also circling the drain.

The crisis of institutional authority has been brewing for a long time, but it is clear that we have entered a new and acute stage. If I can sift all this down to a single fact, what we have learned over the past 20 or so years is that those institutions we thought were built on a sound foundation were in fact resting on sand, and had in fact been undermined for years. Those who we assumed had our best interests in mind do not; they are cynical operators, in it for their own power and gain.

The fall of a great institution always seems sudden, but its causes are usually of very long standing.

And what all of these crumbling institutions and their leaders all seem unable to grasp is that they are entirely responsible for their own demise. They continue to this day to blame their difficulties on external factors, completely blind to the reality that they no longer live in a society that trusts or believes anything they have to say.

Our political and media establishment claims that “election denial” and “radicalism” are the greatest threat to our political order. This is complete nonsense. These kinds of things are symptoms of a greater problem, the inevitable result of decades of mismanagement, when people no longer trust our political institutions or the people who run them.

Similarly, the church looks at the world and blames “secularism” for the wholesale abandonment of religion. Rubbish. It is not atheism or secularism that have driven so many people away from the church. It is corruption within, so acute that, for instance, generations of Episcopalians grew up under pastors who did not believe in the scriptures and the doctrines of our faith they were entrusted to teach; or who were morally unfit to lead the church; or who wasted their own and the church’s energy on vain and irrelevant programs and pursuits.

The shepherds themselves have scattered the flock.

So it was in the day of the prophet Jeremiah, who lived in times not so different from ours.

The reading from Jeremiah opens with a declaration of woe, a curse on the authority figures of the day, who have abused their position and their trust, just like so many leaders of today. “Woe to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture! says the Lord. Therefore thus says Lord, the God of Israel, concerning the shepherds who shepherd my people: It is you who have scattered my flock, and have driven them away, and you have not attended to them. So I will attend to you for your evil doings, says the Lord." There is a crisis of authority, of leadership, and God warns that he will intervene on behalf of his people, but this will be a hostile intervention toward those rulers, priests, and authorities who have incurred his wrath. They will be removed and replaced.

Good things are coming for God's neglected and scattered flock. “I myself will gather the remnant of my flock out of all the lands where I have driven them, and I will bring them back to their fold, and they shall be fruitful and multiply. I will raise up shepherds over them who will shepherd them, and they shall not fear any longer, or be dismayed, nor shall any be missing, says the Lord.”

What God promises is not a democratic revolution or ‘regime change’ in the usual sense, but a new and worthy King who will be as worthy, wise, and righteous as their present leaders are unworthy, foolish, and corrupt. He will be the true heir of King David. “The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. In his days Judah will be saved and Israel will live in safety. And this is the name by which he will be called: ‘The Lord is our righteousness.’”

The season of Advent which begins next week is a time when we join the ancient Israelites in waiting for the appearing of this righteous and worthy King. He has already come, and he will come again at the end of days to rule not only over Israel but all of the nations of earth.

In this way, Jesus is the answer, not only to our personal problems, but to the big problems which afflict us as a society. It is he who sets up rulers and puts them down; he reigns now from heaven, and all the nations are judged in his sight.

When we pray for our own leaders, we pray that they would imitate Christ in wise and righteous rule. We pray this because we know that they will be held accountable to him for how they have acted. Forget about the court of public opinion; the accountability our elected officials, judges, and priests should fear above all is not the people but the unquenchable fire of divine wrath. There will be, literally, hell to pay, both in this life and in the next.

Over the next four weeks of Advent, I will be preaching on what the Church calls the "four last things," which are the subject of traditional Advent sermons: the four last things are Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell. As I explore each of these four related subjects, I will seek to help us meet Jesus in each of them, and show how his promise of salvation is worked out in the midst of these scary and upsetting facts (and yes, I include Heaven along with the other three in the category of scary and upsetting, as you will see!)

But today, as we observe the solemnity of Christ the King, or the Reign of Christ, fix your eyes on the one who reigns even from the accursed tree. The repentant criminal said, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom." But Jesus did not promise to remember him at some future point when he would enter into this kingdom. He said, "Today you will be with me in Paradise." Though tortured and bleeding, dying, crowned with thorns, Jesus was consolidating his rule; even at that moment he was achieving victory over the enemies of his people; over their corrupt rulers, over their unholy priests, and over the spiritual forces of wickedness which lie behind the visible evils of the world. Even death and hell could not stand before him; those tombs of the righteous, which Jesus accused the religious establishment of building for those their fathers had killed, trembled and gave up their martyred dead.

Even on the cross, Jesus was fully revealed as the anointed one of Israel, the son of David, and the great high priest, the seed of Abraham in whom all nations would be blessed, and the seed of the woman who would crush the serpent.

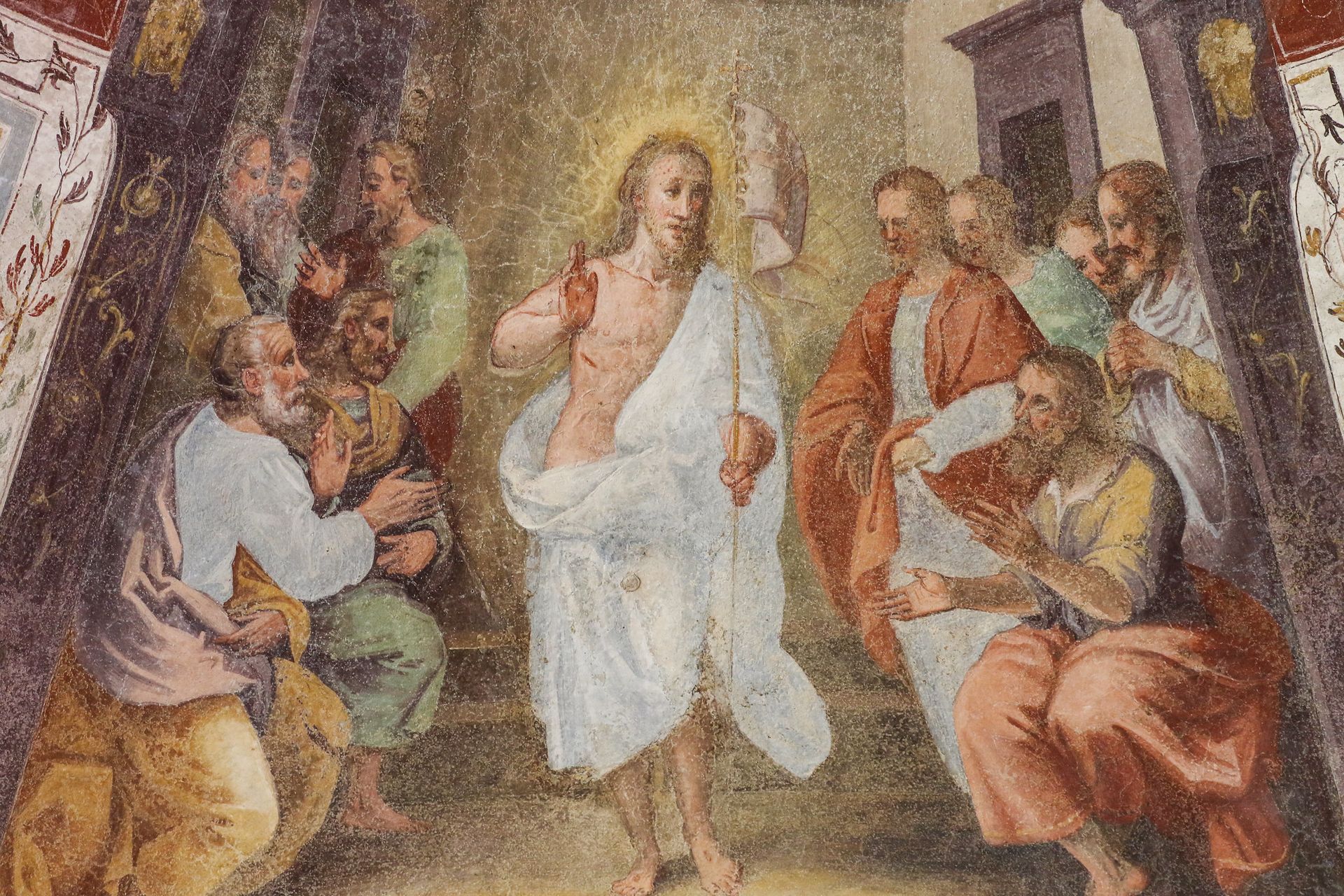

The icon of Christus Rex, “Christ the King,” which looms behind this altar, must be more than a static image, a figurehead like the carved mermaid on the prow of a boat. It must not represent a future hope only; far less should it be viewed as an aspiration for what the world might look like if we simply tried harder. No! If Christ the King were simply the totem of something we desire to create for ourselves in the world, that would be idolatry. Christ the King means that Jesus Christ rules over the nations now, in actual fact, as well as over the Church, despite her low condition. Only if we truly believe this, can we pray faithfully, as he has taught us: Thy kingdom come; thy will be done, on earth, as it is in heaven.